Love, the Heron – 5 April 2025

I should like to live in Julian Barnes’s Benign Republic. Its principles, set out in his new essay, Changing My Mind, seem reasonable and clear and include full restoration of all arts and humanities courses at schools and universities. I shall let you discover its other commitments and then, perhaps, we can disagree about them. I may change my mind. You may change yours. Our minds may change us. Our memories of the discussion will vary. In time and with age my strong opinions may transform or become more weakly held or the opposite.

It is a fascinating essay on memory, words, politics, books and time and the nature of changing one’s mind in relation to these. On E. M. Forster, Barnes is pleased to have changed his mind. On a few matters, he has not, including the primacy of love and the primacy of art, and the belief that literature is the best system we have of understanding the world.

Hallie Rubenhold’s Story of a Murder is an intelligent demonstration of this. Ignore announcements that this is ‘a retelling’, ‘true crime’ and the story of an ‘infamous murderer.’ It is a meticulously researched account of the life and death of Belle Elmore, a woman murdered by her husband in 1910 and the investigation and trial that followed. It is an analysis of how Belle, her murderer and his lover have been presented in the years since then and why. For, despite being found guilty, Hawley Harvey Crippen has been portrayed as a figure of sympathy, his relationship with his typist a true love story and his wife a grotesque woman standing in their way (whilst daring to expect her husband to fold his own clothes).

Rubenhold’s writing makes this a captivating story but it is not sensationalised. I learnt about class, travel, communication and laws in America, Canada and the UK in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and was compelled not by grisly details but by Rubenhold’s deep study into how the case unfolded and her arguments about what Belle Elmore came to represent, about the invention of a monster to put women back in their place.

While this may be about who gets to tell their story and giving a voice back to Belle, I think it’s more than that: it’s about how to listen, read and think critically.

The Sleep Room by Jon Stock is, in part, about affording the victims of a story of medical abuse their voice. But the book is careful to separate their accounts, several of which are printed verbatim, from Stock’s scrutiny of the man responsible, William Sargant. For years, Sargant was allowed to experiment on psychiatric patients, putting them into insulin comas, inducing narcosis, subjecting them to electroconvulsive therapies and lobotomies.

Together Stock’s analysis and the testimonials make one consider the figure of Sargant critically, not caricaturing him as a devil but instead showing how a man was lauded for what should have been recognised as dreadful crimes.

Language is slippery and it matters to understand who is telling a story and why. Natasha Brown assesses this brilliantly in Universality.

The novel begins with an article about a group squatting in a farmhouse planning their utopia, the owner of the property, a wealthy banker living in his South Kensington flat unbothered by having left a solid gold bar on the mantelpiece of his second home and the mother of a lost young man, who has used that gold bar to batter someone over the head. How one reads the article and judges its characters will change vastly over the course of the book though in what way will, I think, differ for each reader.

The interweaving of many languages – spoken and visual – in The Naked Eye by Yoko Tawada is complex and profound. I’m currently reading this novel about a young woman who travels from Vietnam to East Berlin to speak at a youth conference. She is abducted and held prisoner, escapes to Paris, finds shelter first with a sex worker, then with a Vietnamese woman and ultimately with Catherine Deneuve – she spends every day at the cinema, watching her films repeatedly.

The author was born in Tokyo, lives in Berlin and wrote the book in both Japanese and German. In Germany, the character tries to speak Russian to her kidnapper. In France, she finds it painful to utter even her own name to the Vietnamese woman who takes her in. In the cinema, she cannot understand what is said and watches the films the more acutely because of this.

Who ought to tell a story? Who gets to set the record straight? Well, in Jakob Wegelius’ book, it is Sally Jones, a very clever (though mute) ape who has just fixed a typewriter in order to do so. The Murderer’s Ape is superb. Sally Jones and her friend, the Chief, run a cargo ship. But when they take on a job from a rather murky character things go drastically wrong.

Who ought to read a story? Well, this is aimed at middle-grade readers but I honestly think it’s splendid for anyone looking for a creative plot, written shrewdly.

Clem Fatale has Been Betrayed by Eve Wersocki Morris is another excellent story of a young (in this case, human) woman embroiled in a wild crime story though here the heroine is not quite so innocent herself…

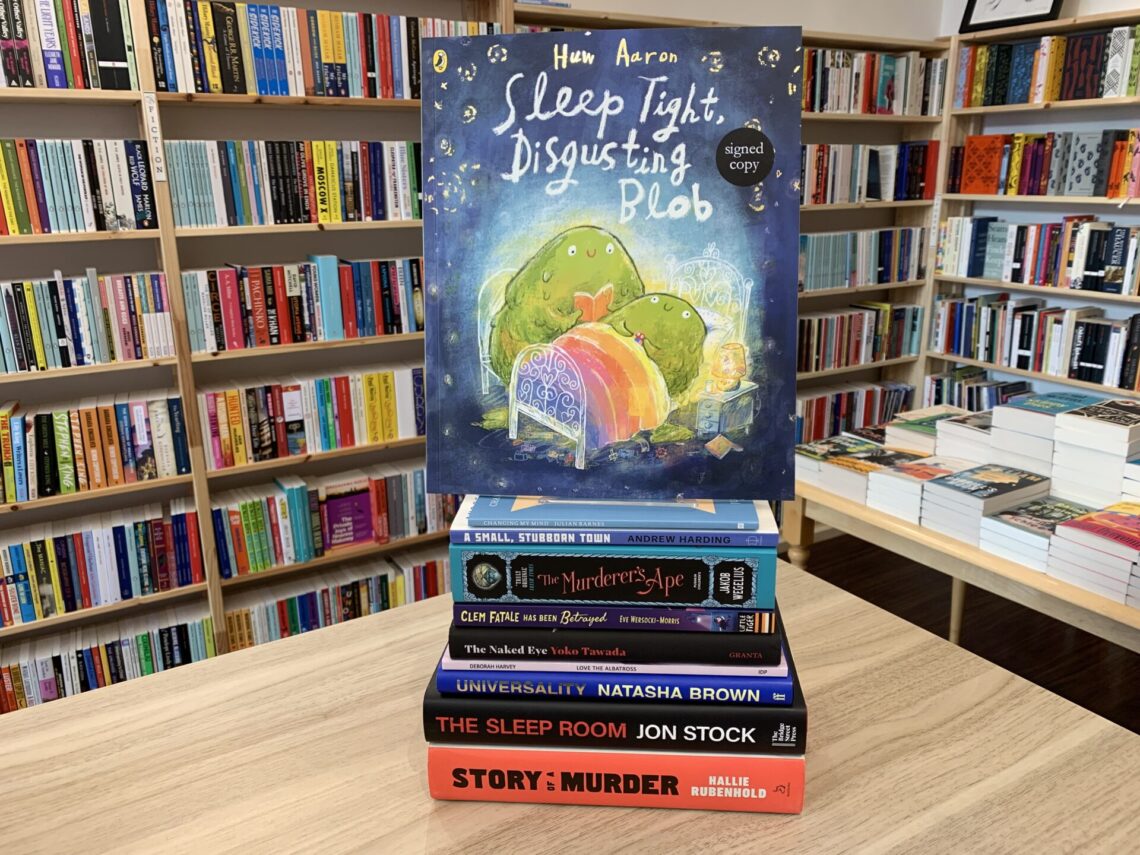

If, after all those forays into crime and language, you are rather tired, perhaps it is time for bed. All I can say is, Sleep Tight, Disgusting Blob. Do come and see our slimy, blobby window celebrating Huw Aaron’s perfect picture book.

Next week, as well as our usual book groups, we are looking forward to two events:

On Friday 11th at 7pm, Andrew Harding will be speaking at the Clifton Library about A Small, Stubborn Town: Life, Death and Defiance in Ukraine, the story of the occupants of Voznesensk and how their response to the Russian invasion in March 2022 changed the possible course of the war.

On Saturday 12th, join us at 5pm in the shop for a poetry reading from Deborah Harvey. I so admire her poetry and her latest collection Love the Albatross is exquisite. Deborah’s performance always adds to the experience of reading her work so I strongly encourage you to come. If you aren’t usually a poetry reader, I suspect this event will change your mind.

May your weekend bolster a belief in the primacy of love and art,

Lizzie

Featured in the newsletter

-

Story of a Murder: The Wives, the Mistress and Dr Crippen

£25.00 -

The Sleep Room

£25.00 -

Universality

£14.99 -

The Naked Eye

£14.99 -

Clem Fatale Has Been Betrayed

£7.99 -

Love the Albatross

£11.00 -

The Murderer’s Ape

£9.99 -

Sleep Tight, Disgusting Blob

£7.99